Biodiversity: The next frontier for tokenized markets

Contributor Kristin McDonald takes a deep dive into the role of biodiversity in tackling climate change and opportunities for web3 to transform future markets.

When it comes to the environment, public discourse centers so strongly around reduced emissions and carbon sequestration that for many, “climate change” has become an analog for the environmental crisis as a whole.

While the urgency of climate change will continue to necessitate a strong focus on decarbonization, the reality is that it is only part of a series of cascading, interlocked environmental crises that increasingly threaten our species’ ecological and socioeconomic stability. Solving the ecological crisis, including climate change, in any sort of permanent way requires us to step back and take a broader systems-level approach that extends far beyond just limiting emissions.

The Importance of Biodiversity

Biodiversity underpins the supply of nearly every major ecosystem service on earth and as such is fundamental to the livelihood and well-being of our planet and species.

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) defines biodiversity as “the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine, and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species, and of ecosystems”

A higher number and density of species increases an ecosystem’s productivity, as extensive inter-species competition and the resulting niche complementarity maximizes the capacity for output from a constrained set of potential resources.

This in turn supports key ecosystem services such as nutrient cycling and soil formation, primary productivity, pollination, carbon sequestration, climate regulation, water purification, storm, flood and drought regulation, and human provisioning (food, water, fuel), including new genetic and chemical materials that are increasingly important for healthcare and agriculture.

Not only does biodiversity increase productivity and support a number of ecosystem services, it also is critical for helping ecosystems remain resilient and adaptive, because variability increases an ecosystem’s or a species’ resistance to threats like disease and changing environmental conditions (think of the impact of a disease in a field with a monoculture vs a polyculture, or an ecosystem’s ability to survive climate change if its flora has the same vs varied temperature requirements).

In this sense biodiversity can act as a tool for both slowing climate change (since it increases primary productivity, sequestering carbon) and for helping our ecosystems adapt to its inevitable impacts. This is true for both natural ecosystems and built ones, as biodiversity (including genetic diversity) is fundamental to the resilience of our agricultural systems.

Biodiversity as a Commodity

Of course, these ecosystem services supported by biodiversity add real (and financially impactful) value to our society. It is estimated that the value of biodiversity in maintaining global commercial forest productivity alone is worth $490 billion per year, while the maintenance of pollinator diversity protects up to $577 billion in annual crop output.

Despite the extrinsic value it provides, we are currently experiencing an alarming collapse of biodiversity. The global rate of extinction is at least hundreds to thousands of times higher than it has averaged over the past 10 million years, driven largely by changes in resource use, followed by negative impacts from climate change, pollution, and invasive species.

This tremendous loss of biodiversity is the result of our current global economy’s inability to internalize the value created by these kinds of ecosystem services.

In many ways biodiversity resembles a public good, which markets are traditionally bad at providing. But unlike traditional public goods, biodiversity levels are determined by the decisions made by millions of private stakeholders, and can’t easily be dictated by a single governing body. Those private decision makers are not incentivized to preserve biodiversity because there is no way to capitalize on the value they create for society by doing so, and the opportunity costs of preserving biodiversity (instead of developing the land for example) are too high. As a result, we lose billions of dollars of economic value through resource exploitation and land use changes that negatively impact biodiversity.

State of the Biodiversity Market Today

Solving the biodiversity crisis means finding ways to internalize the true costs of these activities into our existing economic systems either through regulation or market-based tools, in order to incentivize behaviour that is more aligned with public interests. Today there are a number of existing solutions that attempt to do this.

Bioprospecting (a process whereby pharma companies purchase the rights to explore certain ecosystems for valuable genetic materials) and ecotourism are both multi-billion dollar industries that attempt to privatize a small slice of the benefits related to biodiversity.

Many companies also invest voluntarily in biodiversity conservation or restoration, either in order to appeal to green-minded customers or, in the case of extractive industries, in order to build goodwill with regulatory stakeholders, local communities, and activist groups. This practice has spawned a small but growing voluntary market of biodiversity offsets, which extremely rough estimates size at less than $100 million (for comparison the voluntary carbon markets are around $1.5 billion). Within this category of voluntary offsets, there are very limited regulatory requirements and seldom any external verification that offset conditions are met, beyond the agreed upon rules between the developer and the offset provider.

However the largest impact on biodiversity today has been almost entirely regulatory driven. At least 37 countries (a database on global offset policies can be found here) require some form of biodiversity compensation and in the US, the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act require compensatory mitigation — meaning that any unavoidable damage to a protected species or aquatic ecosystem is offset by compensatory action elsewhere.

In addition to national-level regulation, there are also a number of international organizations and collectives working to set standards or provide guidance on biodiversity protection and offsets, including the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the World Bank, and the World Conservation Union (IUCN), among many others. Together, these efforts feed a roughly $10 billion market for compliance-driven biodiversity offsets.

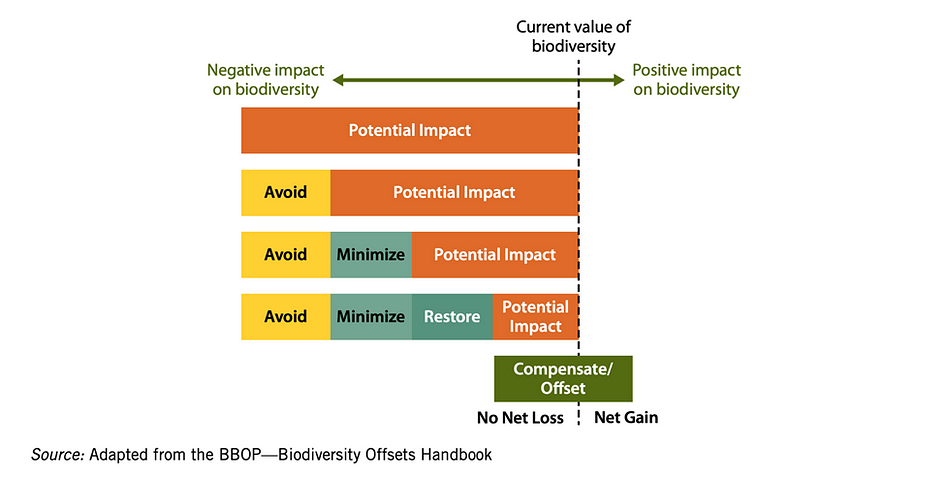

Based on the work done by these organizations, a policy of “no net loss” has become an international standard — meaning that developers must offset their impacts to biodiversity losses elsewhere, after first taking actions to avoid biodiversity loss following the “avoid, minimize, restore” hierarchy.

Creating or implementing a biodiversity offset requires a number of stakeholders that may differ dramatically depending on the type of biodiversity offset, whether it is compliance or voluntary, and what region it is in. Usually companies interested in purchasing an offset (either because they want to or because an Environmental Impact Assessment revealed they were required to do so) hire third party consultants, who in turn depend on private agencies to identify willing landowners, conduct or supervise the restoration action, and then verify these credits with a government agency. The scope of an offset can range from as broad as setting aside a certain acreage of land for conservation to as specific as carrying out direct actions to increase the population of a certain species.

The process is complex and high touch, often requiring cross-sector and cross-border communication. In addition, biodiversity projects require accurate baselines to be established as well as ongoing measuring, reporting and verification (MRV), which almost always requires on the ground surveys that are expensive and logistically complex.

Given the high costs of developing one-off offsets on a project by project basis, there is increasingly a move towards aggregated biodiversity offset systems that seek to reduce the costs of implementation. These include mitigation banks (which usually “collect” offsets from privately owned conservation projects and then sell them to project developers via a broker) or various methods for donating to existing biodiversity projects. Because the purchased offsets are usually bespoke, these methods are most often used in the voluntary markets where offset requirements are less stringent.

In theory, biodiversity offsets are a market instrument that internalizes the value of biodiversity into our actions by ensuring that we pay the cost of creating (or protecting) the equivalent value of any lost or degraded biodiversity elsewhere. In practice however, implementations and outcomes vary widely. Regulation or standardization is limited and differs greatly across markets and organizations, and the expensive and logistically complex MRV process impedes and disincentivizes the pursuit of high-quality outcomes, all of which has resulted in a historically constrained market.

The Biodiversity Market of Tomorrow

Over time as the value of biodiversity and the impact of its accelerated loss becomes more apparent, it is likely that both regulatory and public pressure for its conservation and restoration increases.

Already many in the industry are seeing signs of inflection in the voluntary biodiversity market that are reminiscent of the evolution of the voluntary carbon markets (which grew 190% in 2021 and are expected to hit ~$50bn by 2030). Companies like Nestle, Salesforce and Bayer are moving beyond net zero commitments to nature positive ones, and are just now beginning to tap into a relatively nascent biodiversity market to try and figure out how to fulfill those commitments, creating new demand and momentum in the industry.

Responding to that demand in an effective manner will require us to increasingly move towards biodiversity offsets as scalable, commoditized assets. That means aggregated biodiversity offset systems, where offsets can be planned and implemented at scale and then “sold” to project developers in a fungible way.

This would allow us to dramatically reduce the transaction costs and logistical challenges of designing and implementing new offsets, which would in turn increase buyer participation in the market, driving up funding. It would also allow us to apply clearer standards, since they would be structured at scale and not on a one-off basis. This would increase the overall quality and efficacy of offsets produced and again further increase participation. And finally, an aggregated approach would allow us to more effectively address the crisis by taking into account cumulative demand and its impacts, and pricing offsets accordingly.

If we’re able to do this effectively — create standards and systems for at scale biodiversity offsets — one could easily imagine a thriving voluntary (and perhaps eventually compliance) biodiversity offset market that resembles the carbon market today. It would be the first step towards creating economic systems that internalize the value of our planet’s ecological health beyond just carbon emissions, something that is critical if we hope to meaningfully change our planet’s current trajectory.

Biodiversity on-chain

There’s been a tremendous amount of innovation in the carbon markets in the past 10 years, most recently the ReFi movement and the advent of on-chain markets, and as we now see signs of a comparable voluntary biodiversity market beginning to emerge, it makes sense to leverage this existing carbon infrastructure to accelerate that trend.

In a sense biodiversity already trades in our carbon markets, as voluntary carbon offsets that have biodiversity as a co-benefit represent the highest volume of offsets sold, and fetch premiums relative to offsets without it. It takes no stretch of the imagination to imagine a world where that biodiversity co-benefit is measured, valued and sold separately from the carbon offset it’s tied to. In fact doing so would likely be a net benefit for the carbon markets, as it would ensure that carbon offsets were valued only on the quality of their carbon sequestration, while the biodiversity component would benefit from being held to a real verification standard instead of an amorphous add-on, and would allow projects to attract additional kinds of capital.

Building this biodiversity market on-chain would bring the same level of scalability, trust, and transparency that players like Toucan are trying to bring to the carbon markets. Higher liquidity would ensure more participation, and the reduced barriers to transaction would create greater market access for both suppliers and buyers.

This characteristic is especially important for biodiversity which, unlike carbon, is hyper-local (i.e. while a ton of carbon in Brazil and a ton of carbon in Germany are fungible, the same is not true for biodiversity). This non-fungibility means that creating real impact necessitates a system that can onboard and engage millions of small-scale and disparate stakeholders — something that web3 is especially well-equipped to unlock.

The biodiversity market is also much more immature than the carbon markets, which would mean ReFi pioneers would have a much larger part to play in setting standards and creating market infrastructure. If done well, this could give us the unique opportunity to skip the fragmentation and lack of standardization that plagues the carbon markets, and potentially create a more liquid, flexible and resilient ecosystem altogether.

The potential to have biodiversity as a programmable on-chain asset would then open up a whole new scope of opportunities. The cost of biodiversity impact could eventually be internalized into development projects, disincentivizing the development of high-biodiversity areas. Consumers (and eventually even regulators) could demand that companies offset their impact on biodiversity knowing that it’s possible to get accurate, measurable outcomes in return. Land owners could implement biodiversity-favorable practices at scale as a source of reliable income, dramatically increasing the value of land regeneration. Biodiversity could become a bankable commodity, with funds owning biodiversity offsets as an asset or a hedge against climate change, and projects selling rights to future offsets to secure financing. A liquid, on-chain market could unlock an entirely new magnitude of capital devoted to protecting biodiversity, and be a building block for creating economic systems that align with ecological ones.

Bottlenecks to scale

Achieving this future means resolving bottlenecks that currently prevent this market from scaling.

Creating an effective tradable biodiversity offset requires us to create market systems that are capable of internalizing the complexity of nature. Biodiversity offsets are plagued with the same additionality and permanence concerns as carbon offsets, but biodiversity is not as fungible or easy to measure and define as carbon is, resulting in new concerns around equivalence (whether or not the offset is creating the same or better biodiversity value that is being lost).

The biodiversity of ecosystems, ecological functions, species, and genetics all represent different kinds of non-fungible ecological value, and biologically important issues such as fragmentation and isolation of habitats must be taken into account when assessing quality.

Biodiversity offsets also usually involve more uncertainty around implementation risks, measurability of impact, and temporal variability than carbon offsets. Creating a liquid market would require us to define standards for measuring and monitoring all these various characteristics so that they could be transacted upon in a reliable and scalable way.

Of course, getting all of these characteristics exactly right is less important in a market where a purchaser may simply be trying to prove net positive impact, which makes the voluntary markets a great place to start. But even in the voluntary market, equivalent biodiversity offsets purchased by companies looking to offset a specific impact are a large portion of the market. Accommodating that would require us to take many of these nuanced differences and definitions into account and use them to tranche the offsets into “similar enough” categories to be fungible, which will create fragmentation and lower liquidity.

Not only is biodiversity more complex to define than carbon, it is also much harder to measure. The MRV component of biodiversity relies on recurring expensive and labor intensive surveys and complex data collection and statistical analysis to establish baselines and prove demonstrable outcomes. This process does not scale well, and creates a bottleneck to supply that would quickly impede liquid biodiversity markets.

And finally, the number of stakeholders involved in implementing a biodiversity offset often vary significantly, and effective methods for engaging them in the process would be necessary to ensure the offsets are being implemented in an effective way and to limit potential concerns around environmental justice.

A Market on the Cusp

While there are still challenges to scale, with increased demand comes increased incentive to innovate, and we’re already starting to see the initial signs of an ecosystem and supply chain come together that could eventually support a more liquid biodiversity market.

On the MRV side, a new generation of researchers, technologists, and entrepreneurs are working to figure out ways to scale the collection of biodiversity data. Salo uses precision satellite imagery, remote sensing and advanced ML to assess high-level ecosystem health, in order to better direct on-the ground resources. Pivotal uses drones, acoustics and image sensors to monitor plant and animal life in detail on the ground, then, under the direction of expert ecologists, applies ML and statistical models to estimate biodiversity levels. And organizations like SimplexDNA, NatureMetrics, and VigilLife are pioneering the use of environmental DNA (aka eDNA, the genetic samples from plant and animal life left behind in samples of soil, water and even air) to even more efficiently and granularly catalog an ecosystem’s biodiversity.

And just as biodiversity markets could leverage the infrastructure of on-chain carbon markets, there are likely also synergies with recent carbon MRV innovation. Companies like TreeSwift are using drones, LIDAR and computer vision to better measure forestry biomass and carbon sequestration, and could potentially evolve to measure more complex biodiversity data as well. Gaia equips foresters with tools to measure carbon data and Open Forest Protocol has a network of validators to confirm forestry information — both networks could in theory be leveraged to collect and log information about biodiversity, or could provide a template for similarly equipping local communities to participate in and benefit from biodiversity MRV.

The revenue stream provided by carbon offsets and the growing value of land has also resulted in a noticeable surge in project developers and investors looking to regenerate land at scale (players like Farm and Cultivo, among others). This means there is a new supply of often tech-forward decision makers willing to experiment with and implement new techniques and go-to-markets for biodiversity offsets, creating a unique sandbox opportunity and initial source of supply for the new market. For many of these players biodiversity offsets represent a higher quality source of revenue than carbon offsets, since increasing biodiversity levels almost always results in a net positive impact to their land, while the same is not always true for carbon offsets. And at the same time, players like Cecil and Vibrant Planet are building tools to help landowners and project developers better manage their natural assets, including more standardized and automated data collection, in order to help scale the implementation of nature-positive programs.

While much of this technology is still early, what we’re seeing is the foundations of an industry that will eventually be equipped to service the needs of a robust biodiversity offset market. However, we shouldn’t wait for that industry to mature before we start to build that market. Technological progress takes time and by working now to create both standards and demand for high quality biodiversity offsets, we provide the framework and the fuel necessary to spur continued innovation.

Looking towards the future

Our environment is the amalgamation of millions of complex entities and their interactions; finding ways to develop sustainably requires us to step back and take a systems level approach to its management. As we build new on-chain infrastructure for carbon markets we’re faced with the exciting opportunity to push beyond just carbon to focus on building systems that value ecological health more holistically.

Web3 is uniquely well suited to tackle the complexity that would characterize such a system, while being fluid enough to continuously adapt to a rapidly growing toolset and evolving scientific framework. By taking an active stance in this market now we can play a larger role in establishing the infrastructure and standardization that will be necessary to make it successful, as well as accelerate its current momentum. Over time what started as an on-chain carbon market could very well become the infrastructure for measuring, valuing and incentivizing the regeneration of the ecological health of our planet.

Kristin McDonald is a principal at Eniac Ventures, where she invests in early stage startups. Check out her recent interview on the ReFiDAO podcast.

Toucan is building the technology to bring the world's supply of carbon credits onto energy-efficient blockchains and turn them into tokens that anyone can use. This paves the way for a more efficient and scalable global carbon market.